When you are helping people begin their recovery, all of your instincts tell you to act like a sports coach. You want the addict or alcoholic to feel empowered, prepared to fight against the strength of their addiction, and ready to beat the odds. So often they begin from a broken place, and your prayer is that they will experience the healing necessary to push back against their cravings and emerge victorious. Our role models come from “Remember the Titans” and “Chariots of Fire,” and our language grasps adjectives designed to inspire and encourage.

When you are helping people begin their recovery, all of your instincts tell you to act like a sports coach. You want the addict or alcoholic to feel empowered, prepared to fight against the strength of their addiction, and ready to beat the odds. So often they begin from a broken place, and your prayer is that they will experience the healing necessary to push back against their cravings and emerge victorious. Our role models come from “Remember the Titans” and “Chariots of Fire,” and our language grasps adjectives designed to inspire and encourage.

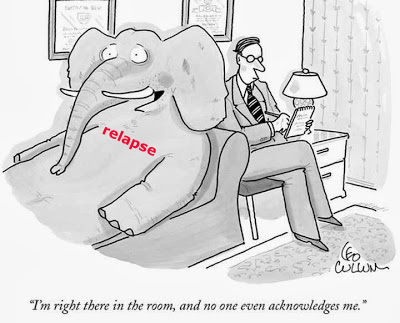

From this perspective, it is hard to think about relapse, and even harder to talk about it. Isn’t this a sign of failure? If we discuss relapse are we not conceding defeat? Do we strip away all important motivation if we talk about the possibility that drugs and alcohol could win another round? All too often the possibility of relapse is the elephant in the room that everyone wants to ignore.

As difficult as it is to talk about both the victories and the losses that are found on the road to recovery, we do no service if we focus only on the bright side. Relapse happens, and by ignoring it we actually weaken the person who is striving to succeed. To avoid a future descent into the abyss of drug and alcohol abuse, the person in recovery must know what to do if they find themselves dangling on the edge.

You may recall the heroic effort of the Olympic skater who fell hard and smashed into the boards at the Sochi Games. He lay on the ice for a few seconds, not moving, and the audience thought his skating was over. But he got up and continued as if nothing had happened, completing his routine to a standing ovation. While we want everyone in recovery to succeed, we want them to know how to get up if they fall during their journey.

A peculiar human tendency is the common assumption that if we slip we have failed. I know a woman strongly committed to a diet designed to help her overcome obesity and regain her health. She was doing very well and was justly proud of her accomplishment. One day she lost her resolve and ate a large piece of cake that was not on her diet. A brisk walk around her neighborhood would have addressed the extra calories with no harm done. However, she immediately admitted defeat; she had failed, and soon began to eat in excess, regaining all of the lost weight.

A peculiar human tendency is the common assumption that if we slip we have failed. I know a woman strongly committed to a diet designed to help her overcome obesity and regain her health. She was doing very well and was justly proud of her accomplishment. One day she lost her resolve and ate a large piece of cake that was not on her diet. A brisk walk around her neighborhood would have addressed the extra calories with no harm done. However, she immediately admitted defeat; she had failed, and soon began to eat in excess, regaining all of the lost weight.

We must help people recovering from addiction prepare so that if they slip their descent is not long and hard. They must be helped back on their feet, continuing their journey toward a better life. Relapse provides a brief moment to learn from one’s errors and keep moving forward — but this rarely happens without preparation. A critical piece in every recovery must be the plan for what to do in the event of relapse. If you fall, how do you get up and continue? Whose help will you need to avoid turning a lapse into a perilous crash?

I suggest an essential part of every recovery program is a “relapse plan.” What happens if you being to use drugs and alcohol again? The strategy must be prepared in advance and ready for action, because there is very little time between wrong action and the descent into a full-blown addiction.

A relapse plan has three main components. It must have support people ready to take action at the first sign of relapse. It must have consequences that are clearly spelled out. And very importantly, the person in recovery must give authority to their support people to “do what must be done” to help get the recovery back on track.

Ann’s plan was well thought out. She asked her parents to take her car, stop all support, and inform her friends, sponsor and counselor if she failed a drug test or refused to take one. She also requested that they do nothing to enable her, demanding that she enter a program and pass a drug test before she could reenter their home. Ann asked her sponsor to plan an intervention and get her to a meeting right away. She asked her friends to stand firm, not allowing her to be with them, or to come to them for support until she had her recovery back on track. Her counselor was the “point person,” with permission to speak freely with family and friends. Ann knew that she could not trust her own thoughts when she was using, so she made sure that every door would be closed except the one that led back to recovery.

Planning for relapse is not an admission of defeat, but a way to strengthen the odds for victory. The recovering addict and alcoholic needs to be ready to learn from failure and move forward, rather than allowing relapse to put progress into reverse. The best military plans include a contingency if there must be a retreat. Failing doesn’t mean the battle is over, it just proves that if something is really important, it is rarely achieved without a determined effort to overcome the obstacles encountered along the way.

Michael Campbell, Co-Founder & President, St. Joseph Institute.